This week, we received the sad news from musical pioneers ‘The Prodigy’, that their flamboyant frontman Keith Flint (49) had taken his own life. This happened on Monday 4th of March 2019 at his home in Great Dunmow Essex and followed a recent separation from his wife, alongside a well documented struggle with depression and substance use. I was especially affected by this tragedy as I regularly run parkrun in Chelmsford, an event that Keith had recently joined. I also consider his music, which fused techno, punk and rock as a huge part of my eclectic musical journey that I began in my adolescence. Suicide has unfortunately been a really present topic for me this year, as two of my friends have already lost loved ones to the epidemic in 2019. One was a successful middle aged businessman and the other was a young man who was starting his adult life at University in Manchester.

Keith Flint is another life taken too young and goes along with the all too familiar reports of suicide by men in the UK , his name is added to a growing list of young male casualties that have been fatally overwhelmed by their mental health conditions. This is a position that we find ourselves in far too often, as we still remember the news about Frightened Rabbits singer Scott Hutchison (36) in 2018 and rock singer Chester Bennington (41), who sadly took his own life in 2017. Given these events, I thought it would be fitting to use this as an opportunity to discuss the worrying trend of increased suicides amongst middle aged men like me. Chester’s suicide was one that seemed to emerge from nowhere as bandmates said that they were planning to make videos for their new album, whilst friends commented that at recent meetings he spoke of being happy and enjoying himself. Looking from afar and with no knowledge of his personal circumstances, Chester was a successful singer, liked by friends and fans and was a father to six children. Yet, something was so difficult that he was unable to share how much he was struggling with those around him and ultimately felt the only solution was suicide.

This story is unfortunately not a unique one as fellow singer Chris Cornell (52) took a similar decision few weeks previously after performing on stage for his many fans. It is also a narrative that I have heard many times in my treatment room where men talk about how they are considering suicide or I speak to clients who have lost important men in lives this way. Below is an excerpt from the Telegraph in 2015 that reports on the increase of successful suicide attempts by men like Keith Flint, Scott Hutchinson, Chester Bennington and Chris Cornell…

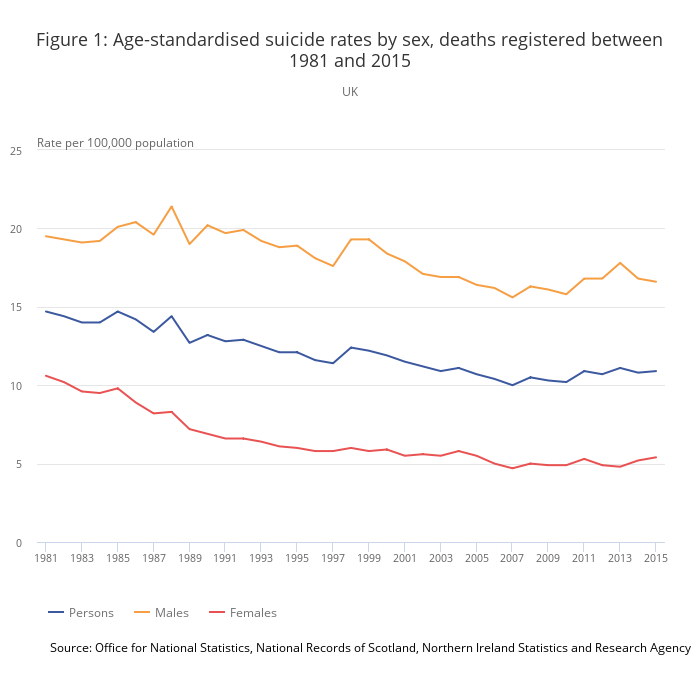

The number of people killing themselves in the UK rose in 2013, official figures have revealed, as male suicides hit their highest rate in more than a decade.

A total of 6,233 suicides were recorded among people aged 15 and over, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) said, up 252 – or four per cent – on the previous year.

The UK suicide rate was 11.9 deaths per 100,000 population in 2013, while the male suicide level was more than three times higher than for females, with 19 male deaths per 100,000 – the highest since 2001.

The male suicide rate in the UK has “increased significantly” since 2007, the ONS said, while female rates have stayed “relatively constant” and been “consistently lower” than in men.

In 1981, 63 per cent of UK suicides were male, compared to 37 per cent who were female.

The UK suicide rate of 11.9 deaths per 100,000 population was last seen in 2004, it added.

Of the total number of suicides in the UK, 78 per cent were male and 22 per cent were female, the ONS said. Some 4,858 male suicides were recorded in 2013, compared to 1,375 female suicides.

The highest UK suicide rate was among men aged 45 to 59, with 25.1 deaths per 100,000 – the highest for that age group since 1981 and the first time that age group has recorded the highest rate.

North East England had the highest suicide rate among the English regions, with 13.8 deaths per 100,000 population, while London had the lowest at 7.9 per 100,000.

Women aged 45 to 59 had the highest female suicide rate with seven deaths per 100,000 population. The female suicide rate across the UK was 5.1 deaths per 100,000.

In England, the suicide rate in 2013 was 10.7 deaths per 100,000 (4,722 deaths), compared with 15.9 in Wales (393 deaths).

Suicide remains the leading cause of death in England and Wales for men aged 20 to 34, accounting for 24 per cent of all deaths in 2013, and for men aged 35 to 49 years, where it accounts for 13 per cent of all deaths.

The suicide rate among men aged 60 to 74 also “rose significantly” from its 2012 level to 14.5 deaths per 100,000 population in 2013. There were 672 suicides among the age group in 2013, up from 562 in 2012 when the suicide rate was 12.3 per 100,000.

In contrast, men aged 15 to 29 were the only age group to record a decrease in the rate of suicides in 2013 to 12.5 deaths per 100,000, compared to 13.6 in 2012.

In previous blogs, I have spoken about how men are somehow disillusioned with their roles being unclear and not as defined as previous generations, and this is one of the factors that academic literature cites as a possible cause of the phenomenon. Other authors discuss that men are less interdependent than women and as a result tend to not share problems as easily or ask for help. My experience is that men will often struggle to seek help and will often be constrained by gendered societal discourses around being strong and that expressions of feelings are weak. Common language such as ‘man up’, ‘grow a pair’, ‘boys don’t cry’ and similar epitomise how men are conditioned by parents, media, contemporaries and each other to not discuss their problems or notice when they need assistance or no who to ask. When I see men who are suicidal, they are often on the surface like the two rock singers mentioned earlier, with family, friends, children and successful careers. On face value they seem to have most of the elements that most of us feel are essential for contentment. It somehow seems easier to understand suicide amongst the marginalised and un-visible in society such as the addicts, homeless and chronically mentally ill, as these individuals are somehow not as representative of our own fathers, brothers and sons and their despair is more accessible as we can easily imagine how their lives may not be worth living.

What seems to be really difficult to interpret is that men who are successful or not completely fractured through substance abuse or trauma can be that unhappy that suicide is their only remedy. My thoughts are that this perceived expectation can also further suppress men from getting help, as why would someone with all these reasons to exist not want to be here? I feel that all men who feel suicidal have internalised a feeling that they have no meaning and that even though others may feel they matter, the suicidal men feel that they don’t and that it is this existential meaninglessness that is fueling the epidemic. Carl Jung describes this sense of loss as a vocational crisis and I believe that this manifests as a feeling of being trapped. If one feels trapped with no escape then it starts to become more understandable that suicide can be one avenue of escape.

I often discuss how suicide impacts families and that many people see suicide as a weak choice, especially with fathers who should somehow be able to rally with the thought that all they are achieving is abandoning their children. My experience is that suicide is an incredibly frightening, brave and usually the only perceived choice, and that to be so despondent and unhappy to even consider it means that an individual is suffering immensely. People often minimise the suffering of individuals by saying that people need to ‘get a grip’ or ‘cheer up’ and ‘do something about it’. These further isolate already depressed people and compound the powerful social construction that those who take their own life were weak or could not be bothered to make themselves better. I often hear men who are severely depressed talk about being unable to connect to the people and things that they love and are usually in bleak, dark and lonely places as their conditions mean that they become shut off from the emotional context of reality.

The moral implications of suicide have long been discussed with English philosopher David Hume writing a seminal piece in the 18th century. He described that suicide is a choice and is a right of autonomous being, he discusses how suicide does not harm society as we stop receiving societal benefits and that we are then free of moral obligation and duties once we make this choice. In some ways, I agree that suicide is the right of the individual but that perhaps if that individual could get help before making the choice, then they may see that other choices are also available and may then pick another. As the selection of only once choice is tantamount to a democracy with one candidate. I believe that men should be able to have opportunity in discussing suicide as a choice but should also be allowed to also reject that choice in favour of another choice to live and that my work has often showed that with the right help we can start to increase our potential choices when we feel trapped.

In order to do this conversations must be had and we must get to point where we can start to be work out our choices before only one fatal choice is available to us.

If anybody resonates with the feelings above, The Samaritans are often the first port of call where men start their journey to not choosing suicide and are a brilliant service that are available 24/7 365 days per year and are free from any phone, even with no credit by calling 116 123. I always advise depressed patients to put this number in their phone as it may be a number that proves invaluable when the world is horrendously dark. Calling this number may be the one extra choice that may just help start a journey to stop the sad figures increasing by one more.

Well written Paul

LikeLiked by 1 person